The Kashmir Valley is a distinct topographic depression in the northwestern Himalayas, formed by ongoing deformation associated with the India-Eurasia collision.

The valley’s origin lies in plate convergence that created the Himalayas and a complex system of faults, folds, and intermontane basins.

This tectonic environment makes Kashmir highly susceptible to earthquakes, reflecting both its geological setting and its associated risks.

Historically, several earthquakes with magnitudes exceeding 7 have occurred along the Himalayan front. The most recent major event in the region was the 2005 Muzaffarabad earthquake (Mw 7.6), which caused more than 80,000 deaths and extensive damage.

A similar-magnitude event would likely produce far fewer losses in countries such as Japan, Taiwan, or the United States, where seismic design is embedded within engineering practice.

This contrast highlights the role of scientific and engineering preparedness in reducing earthquake impacts.

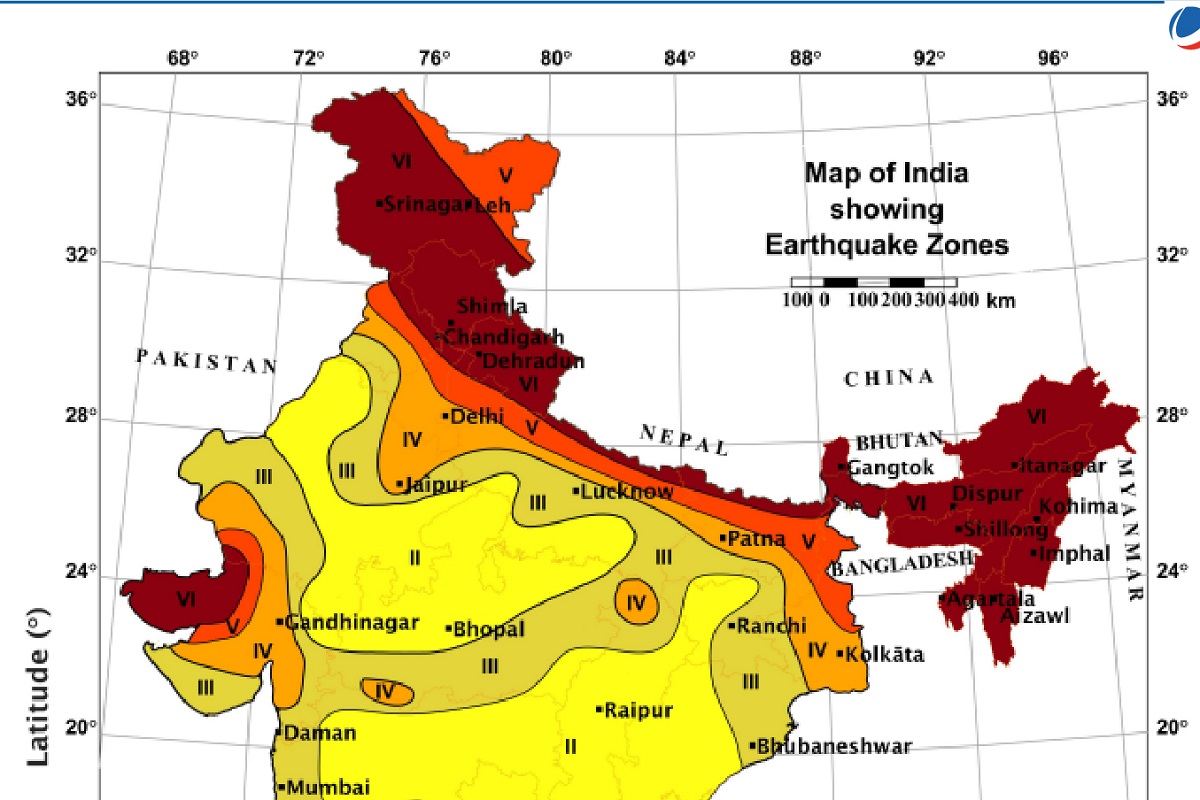

The 2025 national seismic zonation map released by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) recognises the high seismic potential of the Himalayan belt by classifying the entire arc, including Jammu and Kashmir, as Zone VI, the highest hazard category in India.

The updated zonation acknowledges the potential for large earthquakes generated by long-locked segments of the Main Himalayan Thrust and associated structures.

This represents a more realistic assessment of seismic hazard for Kashmir, and has direct implications for its infrastructure safety, planning, and policy.

Seismology consistently demonstrates that earthquakes are natural processes, rather than disasters by themselves.

The long gaps between major events may give an impression of safety, but tectonic strain continues to accumulate.

Disasters occur when vulnerable infrastructure is exposed to strong shaking.

Much of the existing built environment, particularly older urban cores and rural settlements, does not meet modern seismic standards.

Many essential facilities, including schools, hospitals, bridges, transport corridors, and utilities, have not been comprehensively assessed for seismic safety.

Combined with high seismic hazard, this infrastructure vulnerability substantially increases the risk of severe consequences during moderate or large earthquakes.

The revised BIS zonation reinforces these concerns.

Rapid, often unregulated, urban growth has increased building density, including along slopes where shaking may be amplified. The concentration of lifeline infrastructure within narrow corridors further raises the likelihood of widespread disruption during a major event.

Given the updated classification and known tectonic conditions, the need for risk-reduction actions is immediate.

The updated BIS seismic zonation and the IS 1893 (2025) Design Code together highlight the need for a structured, scientific approach to earthquake risk management in Kashmir.

The designation of the region as Zone VI reflects the established tectonic reality of the Himalayan collision system, where large earthquakes are inevitable. Reducing future losses requires strengthening hazard assessment, improving infrastructure resilience, enhancing public preparedness, and expanding monitoring and research.

A critical requirement is the development of detailed seismic hazard maps and microzonation studies for all major urban centres.

These factors must account for active faults, ground-motion amplification, local soil conditions, and slope stability.

Microzonation results should be formally integrated into land-use planning and building-permit processes. Improving active-fault mapping through coordinated geological, geophysical, and geodetic studies is essential, especially where blind or distributed faults may influence future rupture behaviour.

A region-wide seismic vulnerability assessment of existing infrastructure is also necessary.

Buildings, bridges, critical facilities, and lifeline infrastructure should be evaluated using standardised criteria and assigned vulnerability levels to guide retrofitting priorities.

Schools, hospitals, and high-occupancy public buildings require focused attention.

Retrofitting should follow the provisions of IS 1893 (2025), with specific attention to design requirements for Zone VI.

Strict enforcement of the updated IS 1893 code is central to long-term risk reduction. All new construction must comply with revised design spectra, detailing requirements, foundation guidelines, and non-structural safety provisions applicable to Zone VI.

Older structures, especially in high-density or slope-margins areas, should be retrofitted based on their assessed vulnerability. Urban authorities must integrate seismic safety into zoning regulations, hillside development guidelines, and project-approval procedures.

Community-level training, school drills, and clear communication of seismic risk must become routine.

The implications of Kashmir’s placement in the highest hazard category must be communicated to ensure compliance with building codes and implementation of preparedness measures.

Enhanced seismic monitoring and research capacity are equally important. Upgrading the regional seismic network, expanding GPS coverage, and improving real-time data systems will support better understanding of strain accumulation and earthquake recurrence.

Research priorities include Himalayan tectonics, ground-motion modelling, liquefaction and landslide susceptibility, and performance of local building types.

An operational earthquake early-warning system, while not a substitute for structural safety, can provide critical seconds for protective actions in hospitals, schools, and essential services.

India’s revised seismic zonation and the introduction of Zone VI provide a scientifically grounded update of the national earthquake-hazard framework.

However, recognising hazard alone does not reduce risk. Earthquakes become disasters when exposure and vulnerability are high and when regulatory systems do not incorporate scientific understanding.

Reducing future losses requires consistent commitment to accurate hazard mapping, code enforcement, infrastructure assessment and retrofitting, public preparedness, and expanded monitoring and research.

While the tectonic forces shaping Kashmir cannot be changed, their societal impacts can be significantly reduced through sustained, science-based policies and practices.